- Commitments (legally-binding promises to spend money on activities that are implemented over several years)

- Payments (expenditures arising from commitments entered into during the current or preceding years)

|

The EU's budgetary system has developed over several decades in pace with the evolution of the Union itself. It has a number of distinct features and follows several principles. Main areas of the EU budget are:

|

|

| The multiannual financial framework (MFF) |

The multiannual financial framework (MFF) is the EU's long-term budget. It sets the limits for EU spending - as a whole and also for different areas of activity - over a period of at least five years. Recent MFFs usually covered seven years. The long-term budget provides for the financing of programmes and actions in all policy areas, from agriculture and regional policy, to research, enterprise and space, in line with the EU’s long-term priorities.

Policies Initiated by the current infectious disease, which has shaken Europe and the world to its core, the EU put forward a proposal for a major recovery plan. Complementing national efforts, the EU budget is uniquely placed to power a fair socio-economic recovery, repair and revitalise the Single Market, to guarantee a level playing field, and support the urgent investments, in particular in the green and digital transitions, which hold the key to Europe's future prosperity and resilience. The EU will raise money by temporarily lifting the own resources ceiling to 2.00% of EU Gross National Income, allowing the Commission to use its strong credit rating to borrow €750 billion on the financial markets. This additional funding will be channelled through EU programmes and repaid over a long period of time throughout future EU budgets – not before 2028 and not after 2058. |

To help do this in a fair and shared way, the Commission proposes a number of new own resources. In addition, in order to make funds available as soon as possible to respond to the most pressing needs, the Commission proposes to amend the current multiannual financial framework 2014-2020 to make an additional €11.5 billion in funding available already in 2020.

The money raised for 'Next Generation EU' will be invested across three pillars:

|

|

| "The European Union might soon add an additional €64.5 billion to its common budget for 2021-2027. But it comes with fine print"

(Euronews)

"The top-up in February 2024 was for months the object of fierce bargaining among member states, each of whom, mindful of the upcoming elections to the European Parliament, pushed hard to see their wish list come true. The negotiations kicked off in June, soon after the European Commission unveiled its proposal, and culminated in an extraordinary summit on 1 February." Once the gridlock broke, a new figure emerged: the bloc's budget for 2021-2027, worth €2,018 billion in current prices (including €806.9 billion for the COVID-19 recovery fund), will be given an additional €64.6 billion until the remainder of the period. The political deal is a considerable downgrade from the €98.8 billion top-up originally envisioned by the Commission. The executive argued the public coffers had been exhausted by the economic shockwaves of the pandemic, Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the energy crisis, record-breaking inflation and devastating natural disasters, leaving the budget deprived of financial flexibility to react to unforeseen events. But from the very onset, the €98.8-billion draft was met with strong resistance from member states, who would have been compelled to provide more than €65 billion in brand-new contributions. Rising interest rates, sluggish growth and diminishing revenues made the idea of writing such a cheque to Brussels all the more intolerable. Diplomats haggled hard over how to cut down the fresh money to the bare minimum, playing a game of mix-and-match to plug the gaps. So what's new and what's old in the budget top-up? Ukraine Facility: €50 billion

Boosting aid for Ukraine is the raison d'être of the revised budget. In fact, it was the only envelope that leaders left intact. Under the agreement, the EU will establish the Ukraine Facility to provide the war-torn nation with €50 billion between 2024 and 2027 to keep its economy afloat and sustain essential services, such as healthcare, education and social protection. The pot will combine €17 billion in non-repayable grants and €33 billion in low-interest loans, meaning member states will only subsidise the former. The money for the loans will be borrowed by the Commission on the markets and later repaid by Ukraine. Brussels will roll out the Facility in gradual payments to guarantee reliable and predictable financing. In return, Kyiv will be asked to carry out structural reforms and investments to improve public administration, good governance, the rule of law and the fight against corruption and fraud – all of which can help the country advance its EU membership bid. In a small concession to Viktor Orbán, the only leader who opposed the Ukraine aid, leaders will hold a debate every year to assess the Facility's implementation, but this high-level discussion will not be subject to a vote (or possible veto). "If needed," the deal says, leaders might invite the Commission to review the package in two years. If the co-legislators agree swiftly on the regulation that underpins the Facility, Brussels will send Kyiv the first tranche in early March. Migration management: €9.6 billion This envelope survived the negotiations almost unscathed and it's easy to see why: migration management is a key priority shared by all countries, particularly those in Southern Europe who bear the brunt of irregular arrivals. The Commission originally asked for €12.5 billion to cover expenses on border control, relations with the Western Balkans, and the hosting of millions of Syrian refugees in Turkey, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon. The executive said the extra money was needed to realise the ambitions of the New Pact on Migration and Asylum, the holistic reform of the bloc's migration policy that is nearing the finish line. Leaders mostly agreed and granted €9.6 billion. "Migration is a European challenge that requires a European response," they said in the deal. New technologies: €1.5 billion

The EU is intent on being a leading player in the cutthroat race for cutting-edge technologies. For that, it needs money – a lot of money. The Commission designed the Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform (STEP) to finance avant-garde projects and promote EU-made high-tech. STEP was designed to help all member states, from the richest to the poorest, access much-needed liquidity in equal conditions. Von der Leyen initially asked €10 billion for STEP to reinforce ongoing programmes like InvestEU and the Innovation Fund. But leaders shot down the idea and allocated only a meagre fraction: €1.5 billion to prop up the European Defence Fund (EDF). Unforeseen crises: €3.5 billion

Since the early days of 2020, the bloc has been engulfed in back-to-back crises. From a lethal airborne disease to floods and fires that wrought untold havoc, Brussels has had a hard time adapting its tight budget to a ballooning list of expenses. In its original proposal, the Commission requested €2.5 billion to bolster the Solidarity and Emergency Aid Reserve, which is triggered to deal with major natural disasters, and €3 billion for the Flexibility Instrument, which, as its name suggests, can be used to respond to any sort of critical situation. Despite the worsening effects of climate change and a strong diplomatic push from Greece, a country badly hit by wildfires, leaders did not go all the way: their deal earmarks €1.5 billion for emergency aid and €2 billion for the Flexibility Instrument. Interest payments: zero

As a result of the aforementioned crises, the EU had to press the pedal to the metal on its joint borrowing, most notably to build the COVID-19 recovery fund. The €800-billion plan, which will be rolled out until 2026, comes with a considerable bill of interest payments, which drastically swelled as inflation hit double digits and the European Central Bank retaliated with consecutive rate hikes. Facing a lofty invoice, the Commission pleaded with member states to add €18.9 billion to the budget review, an amount that immediately raised eyebrows. (The figure to cover overrun costs is variable and is now estimated at €15 billion.) In the end, leaders opted for a three-step "cascade mechanism." First, money will come from the existing provisions within the recovery fund. If this is not enough, Brussels will draw funds from programmes that are underperforming and the Flexibility Instrument. If this is still not enough, the third step will kick in and create an instrument financed by "de-commitments," financial envelopes that were unspent or cancelled. Only when all of this has failed will the cascade hit leaders as the Commission will be entitled to ask member states to provide direct contributions. Redeployments: €10.6 billion

All the numbers listed above make a total of €64.6 billion but there's a catch: countries will only cough up €21 billion. How is it possible? Besides the €33 billion in loans from Ukraine, which involves the Commission and Kyiv, member states decided to shift €10.6 billion from ongoing EU initiatives: €4.6 billion from Global Europe, €2.1 billion from Horizon Europe, €1.3 billion from assistance to displaced workers, €1.1 billion from agriculture and cohesion funds, €1 billion from EU4Health and €0.6 from a special reserve to cushion Brexit disruption. Speaking on condition of anonymity, a senior Commission official said the overnight cuts to Horizon Europe, the bloc's flagship research programme, and EU4Health were unfortunate and "difficult to swallow." "At this point in time, it's impossible for us to really tell you what this will mean in practice," the official said about the potential effects of the €10.6-billion redeployment push. In the case of EU4Health, the chop represents about 27% of the money left in the envelope, established less than four years ago in response to the pandemic. The demanded changes to both Horizon and EU4Health are likely to enrage the European Parliament, which needs to co-approve the budget review. "This is something that is not easy," the senior official added. But "we will religiously follow what the legislators decide." |

| COMMENT on budgetary proposals |

|

| DEALS ON EU BUDGET |

|

On 17 November 2016, the Council and European Parliament reached agreement on a 2017 EU budget which strongly reflects the EU's main policy priorities. Total commitments are set at €157.88 billion and payments at €134.49 billion. "The strength of the 2017 EU budget lies in its focus on priority measures such as addressing migration, including by tackling its root causes, and encouraging investment as a way to help stimulate growth and create jobs. This maximises the budget's impact to the benefit of EU taxpayers, European citizens and companies. And it respects member states' continued efforts to consolidate their public finance", said Ivan Lesay, state secretary for finance of Slovakia and President of the Council. More money for migration and security

|

Agreed commitments of almost €6 billion mean that around 11.3% more money will be available for tackling the migration crisis and reinforcing security than in 2016. The money will be used to help member states in the resettlement of refugees, the creation of reception centres, the support for integration measures and the returns of those who have no right to stay. It will also help to enhance border protection, crime prevention, counter terrorism activities and protect critical infrastructure.

Investing in growth and jobs Commitments of €21.3 billion were agreed to boost economic growth and create new jobs under sub-heading 1a (competitiveness for growth and jobs). This is an increase of around 12% compared to 2016. This part of the budget covers instruments such as Erasmus + which increases by 19% to €2.1 billion and the European fund for strategic investments which raises by 25% to €2.7 billion. The 2017 EU budget also includes €500.00 million in commitments for the youth employment initiative to help young people to find a job. Further €500.00 million were agreed for supporting milk and other livestock farmers with additional support measures announced in July. With a view to matching member states' consolidation efforts at national level the Council and the Parliament reminded all EU institutions to complete the 5% staff reduction by 2017 as agreed in 2013.

The 2017 EU budget is expected to be formally adopted by the Council on 29 November and the Parliament on 1 December. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

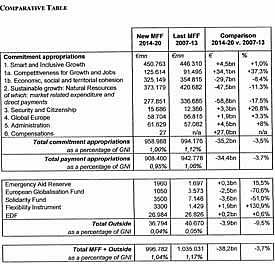

8 February 2013, a deal was reached on the new EU budget. While the focus has been on the overall level of expenditure (which,frankly, was never going to change either upwards or downwards by more than a few percent, in a decision-taking procedure in which every single Member State has a veto), there are some significant changes in the content of spending. Some key points on the deal are:

|

CAP spending will fall by 17.5% compared to the last MFF, but as it is in continual steady deline, it will have fallen by over 20% by the last year of the seven year period (2020), which will leave CAP spending at about 27% of the overall budget - a long way below the 75% it was in the 1970s!

Spending on the growth items (heading 1a, which includes research & innovation, connecting Europe, Erasmus student exchanges, etc) rises by 37.3% compared to the previous MFF, again on a steady trend so that by the final year it will have risen by over 40%. Granted, this is not as much as the Commission had initially proposed, but compared to the current situation, it is a significant improvement. The discrepancy between commitments and payments (the latter are always lower, as commitments can be paid out over several years, for example for big infrastructure projects) is larger than usual, but this is compensated for by flexibility in transferring unused payments from one year to the next, so that there will be adequate payment appropriations to cater for legal commitment. The final deal is seen as victory for those that wanted an austerity-driven budget. With the focus on spending moderation, it reflects strained times. However many warn that the reduced budget could result in an EU with fewer resources at its disposal, limiting its ability to deliver better results for EU citizens. The Summit is declared by EU circles to be a victory for co-operation and consensus since none of the 27 member countries did use their veto. For most countries their national interests were met and as a result leaders could return to their home countries able to claim a victory. Commentaries by institutions of the EU: European Council President, European Council President, Herman Van Rompuy, emphasised in his statement that the budget is ‘future oriented’. Van Rompuy insists it is a budget ‘driven by pressing concerns’. The proposed budget, 3% less than the current EU budget, focuses on balanced growth, the encouragement of new investment and a youth employment programme. The €6 billion allocated for generating youth employment is ‘a powerful incentive’, Van Rompuy says, and has been met with enthusiasm all over the EU. Yet investment in education and regional infrastructure that could help youth employment are among the areas where cuts will be made. Here is the full text of the speech 18-02-2013 from Van Rompuy to the EP. European Commission President, José Manuel Barosso, praised the budget and said it

was a “catalyst for growth” but sees the deal reached as a “basis for negotiations with Martin Schulz, European Parliament President, has openly criticised the budget saying, “the EU budget is for investment”, therefore savings made there are savings made in the wrong place. “The EU budget is money not for Brussels but for ordinary European citizens”. The budget deficit concerns him as there are “more and more tasks and less and less money”. He emphatically declared, “I will not sign a deficit budget, Europe like the US a few weeks ago, is heading for a fiscal cliff”. Other MEPs have also expressed concern. Joseph Daul (EPP), Hannes Swoboda (S&D), Guy Verhofstadt ( ALDE), Rebecca Harms and Daniel Cohn-Bendit (Greens/EFA) attacked the agreed EU budget, saying it may lead to a structural deficit. “Large gaps between payments and commitments will only store up trouble for the future and not solve existing problems,” the leaders of the four European Parliament political groups stated. Joseph Daul, leader of the right-wing European Peoples Party, added that he would vote no to the deal because it is a bad deal for Europeans and said, “To those I can already hear declaring us irresponsible; I say to them simply that what is irresponsible is providing payment appropriations that are lower than commitment appropriations”. The EPP believe this budget will lead to deficit and therefore they will remain firm on this point and as such not endorse it. Brief commentaries by HoSG's: Chancellor Merkel declared that “the effort was worth it” and ensured that the budget would deliver predictability and solidarity, which in troubled times is what the people want to hear after all. “It gives us the ability to plan for important projects and with a view to growth and employment, that's decisive because the security to plan for investors is the precondition for us to even reach growth and employment again”. The Dutch PM Mark Rutte said that “The Netherlands can be content with this result, we kept our rebate”. The French media are clearly not so enamoured. Le Figaro ran the headline ‘Cameron et Merkel imposent l’austérité à Hollande’. Francois Hollande, the French President admitted it was not his dream budget, calling it a ‘good compromise’ but the best he could get under the circumstances. An Anglo-German co-operation for once making France the outsider in negotiations and making Hollande somewhat unpopular with his own voters who were expecting a better EU stimulus package. With regards to the all important CAP, Mr Hollande said that “The relative share of agricultural spending in the European budget will decrease, but I made sure to preserve the funding destined for our farmers”. Italy who had previously sided with France in their desire to curtail cuts seemed content with the budget. Prime Minister Mario Monti said it was, “satisfying” and in terms of Italy’s contributions proved to represent a “very significant improvement”. The Czechs had previously stated that the reduced budget benefited two countries and helped their economies stay afloat at the cost of the rest of the EU. Prime Minister Necas’ threat of veto at the summit meant that although the funds they receive from the EU through cohesion policy will decrease, the Czech Republic will not see as severe cuts as anticipated. The Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk stated that the day the budget deal was reached was “the happiest day of my life” and added that “Poland is the biggest beneficiary of the EU”. Although Spain under the new budget will receive slightly less money, Prime Minister Rajoy was pleased by the deal, which will see Spanish workers benefit from a new fund to create jobs for young workers. Brief commentaries by other institutions: The OECD is concerned and stated that the ‘economic crisis should not be used as an excuse to cut flows to poor countries’. The EU spokesman for Oxfam stated “The consensus reached could have potentially negative consequences on the ability to achieve global anti-poverty goals, especially in Africa, It comes short of what’s needed to tackle pressing global issues, from sustainable development and increasing disasters, to food security and social justice. It will undoubtedly also impact negatively on the ambitions of Europe as a global player”. |

|

29 March 2011, H.E. Mr. Janusz Lewandowski, Eurocommissioner for Budget, lectured on 'Ambition vs. Realism: the European Financial Framework post 2013'. The long-range budget 2014_2020 will be dealt with in June next. ´Young´ EU member states wants to let grow expenditures. That strikes against countries, which hand over more net amount than they will receive (Germany, France, The Netherlands). But Germany and France are being tenacious of the enormous agriculture budget. All blocks are in

the all-round defense position. Dragging a rebate on short term is difficult.

European expenditures 2012 are higher than expected. The same happened with the budget 2011. That delivered a severe fight between European Parliament, that wanted to spend 6% more, and the UK and the Netherlands, who both wants to freeze the budget.

|

|---|

We are cutting on travelling, meetings. Not well functioning programs will be deducted. The total budget for administration costs are only 6%. 8 à 9 miljard from out total 140 miljard. That is a small part

Member states are constantly asking for more European cooperation: immigration, energy, milieu, financial supervision, a diplomatic service. At the same time it is wanted that we will do that with less people and less money. The European government is even as big as the one of Paris. It cannot become smaller. Many cities are expending 20 till 25% on administration. The EU 6%.

The EU has to cut in the remaining part, but the 94% that are expenditures, which are to decide by the member-states. That is not 'Brussels', that are the member-states by themselves. Brussel only take care that their decisions will be executed. |

|

|---|